Consumer Borrowing – Not a Second Shoe

Consumer borrowing remains a concern for many investors. The thought is that people went on a borrowing binge and now the excess has to be undone. In the midst of economic hard times, the argument goes, this can only mean more bad news to come. However, all is not dark

Consumer borrowing remains a concern for many investors. The thought is that people went on a borrowing binge and now the excess has to be undone. In the midst of economic hard times, the argument goes, this can only mean more bad news to come. However, all is not dark

This concern has been repeated often, particularly in recessionary times, only to have the economy enter a growth phase and confound the doomsayers. Their message remained – “It’s only a matter of time!” – but it was drowned out and ignored as everyone else went about their business of living.

There is a problem, but it isn’t with excess borrowing. It’s how the numbers are analyzed. Here are four graphs that tell the story of consumer loan growth over the past 60 years.

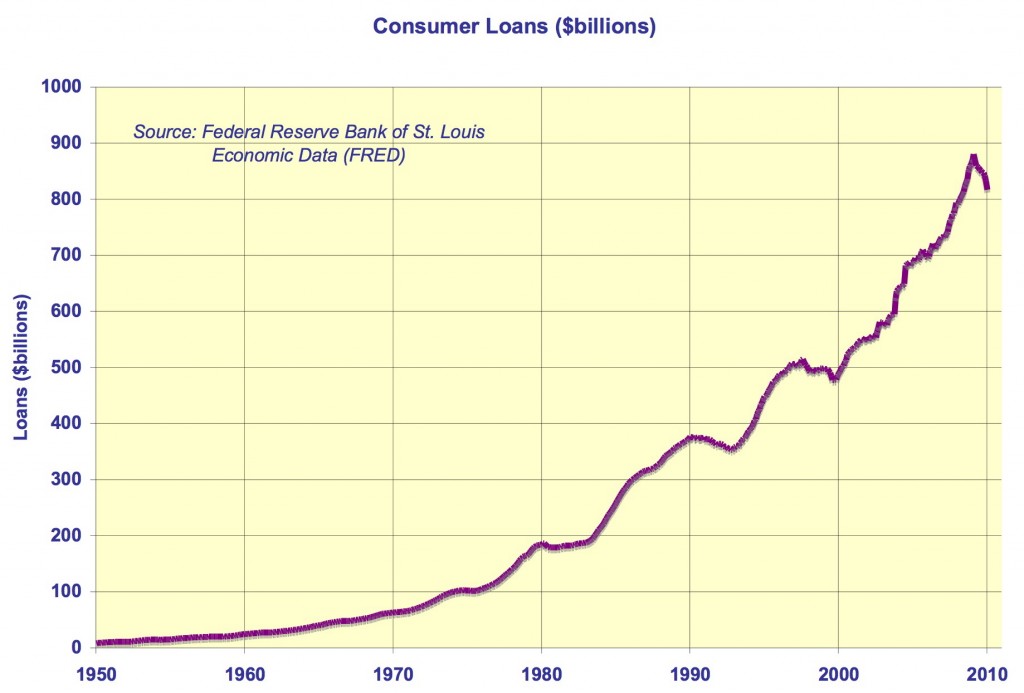

Graph #1 – The scary consumer loan growth using the raw numbers. (Note: These are total individual loans at all commercial banks. They do not include real estate mortgages, nor do they include business [commercial and industrial] loans.)

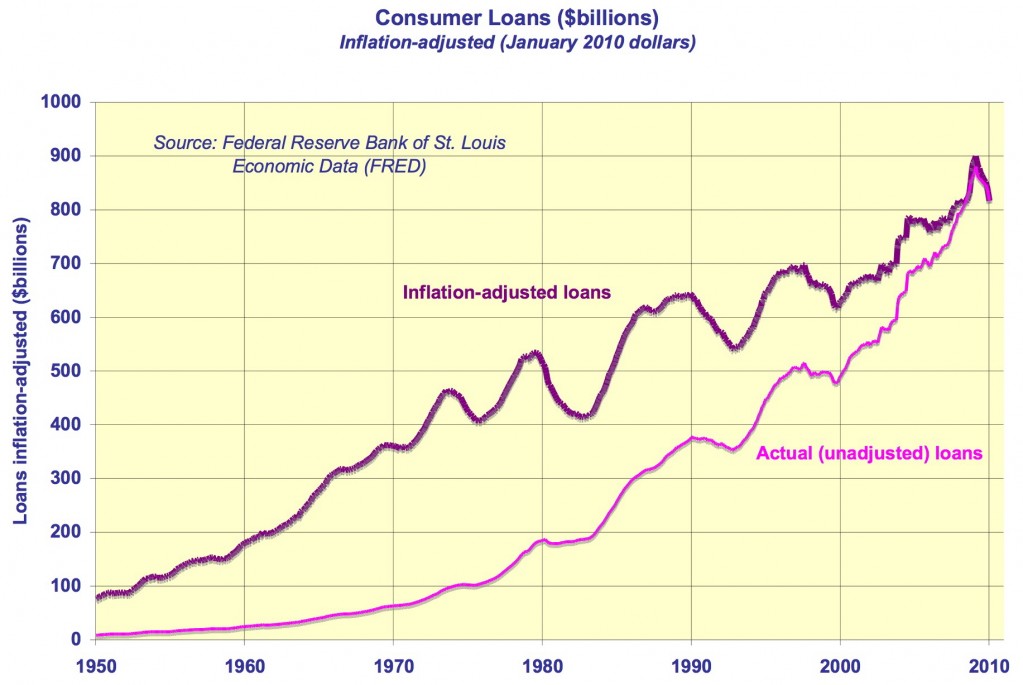

Graph #2 – Those same numbers, adjusted for inflation. Since the older dollars were worth more, those loan balances need to be increased to compare with today’s dollars.

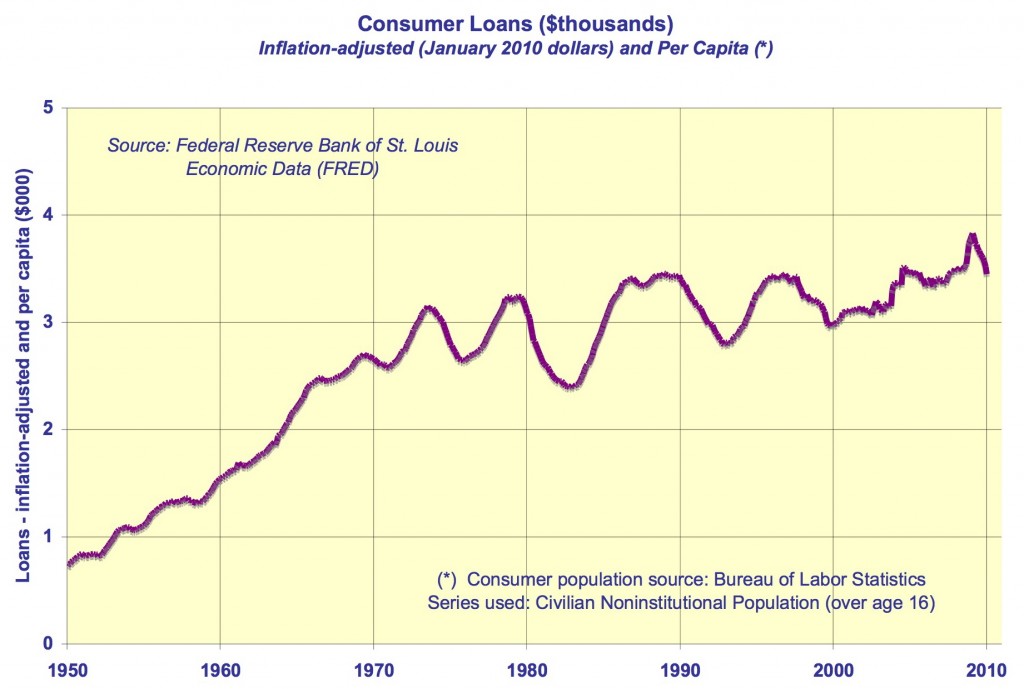

Graph #3 – The inflation-adjusted numbers, per capita – i.e., divided by the “consumer” population (*). After all, even if each consumer has the same loan balance, more people means more total loans.

Graph #4 – Plotting the amounts from Graph #3 on a log scale. This converts growth rates to easily seen straight lines.

Note the two periods of dramatically different growth. The twenty years, 1950-1969, had a combination of drivers: post-war spending (war years saw saving and rationing), the final break from the depression mentality (i.e., the belief that borrowing is bad), and significant income and asset value growth. The period following is one of slow growth, marked by up-and-down trends corresponding to growth and recessionary periods. Note that today’s loans are back to the trend line.

So, while consumer loans might drift lower, it’s best not to expect a sharp decline or a “second shoe” to drop.

– – – – –

(*) “Consumer population” is the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) civilian noninstitutional population, defined as consisting of persons 16 years of age and older, residing in the 50 States and the District of Columbia, who are not inmates of institutions (for example, penal and mental facilities and homes for the aged) and who are not on active duty in the Armed Forces. This is the same group used by the BLS to evaluate unemployment.

If the graph is adjusted for inflation and population growth, why should we expect to see ANY upslope? In fact, why should we not assume that everything since 2000 is part of a bubble and expect to see a decrease to 2000 levels? Not arguing, just asking.

The short answer is that inflation-adjusted, per-capita borrowing can rise in line with real income gains and not create problems. But I am not convinced that that is the answer.

Rather, I’m afraid we reached the limit of analysis that we can all agree on. To fine-tune the numbers further requires getting into areas of gray, such as:

– the effect of other borrowing (e.g., home equity and 401k loans)

– the wealth effect (higher asset values = higher willingness to borrow)

– relative interest rates – pretax and after-tax – and inflation outlook (borrowing can be advantageous at times)

– demographics – e.g., the aging effect

– family formation – (i.e., the effect of excluded children under age 16 on borrowing habits)

– military personnel exclusion from consumer population, but their borrowing being included

– and many other adjustments, I’m sure

Also, the government statistics, while good, are rarely precise enough for in-depth analysis.

So, I am comfortable with the observations we get from the data – namely, that the ski slope growth in borrowing is an inaccurate measure of consumers’ willingness to borrow. Making the two adjustments removes most of the support of the argument that consumer borrowing was out of control. Will we see per-capita borrowing stay at about $3,500 or drop to the $3,000 level? I don’t know. But, I believe wherever the borrowing heads, it will be reasonable and economically viable – not reactionary and destructive.

Thanks for the good question.

John Tobey